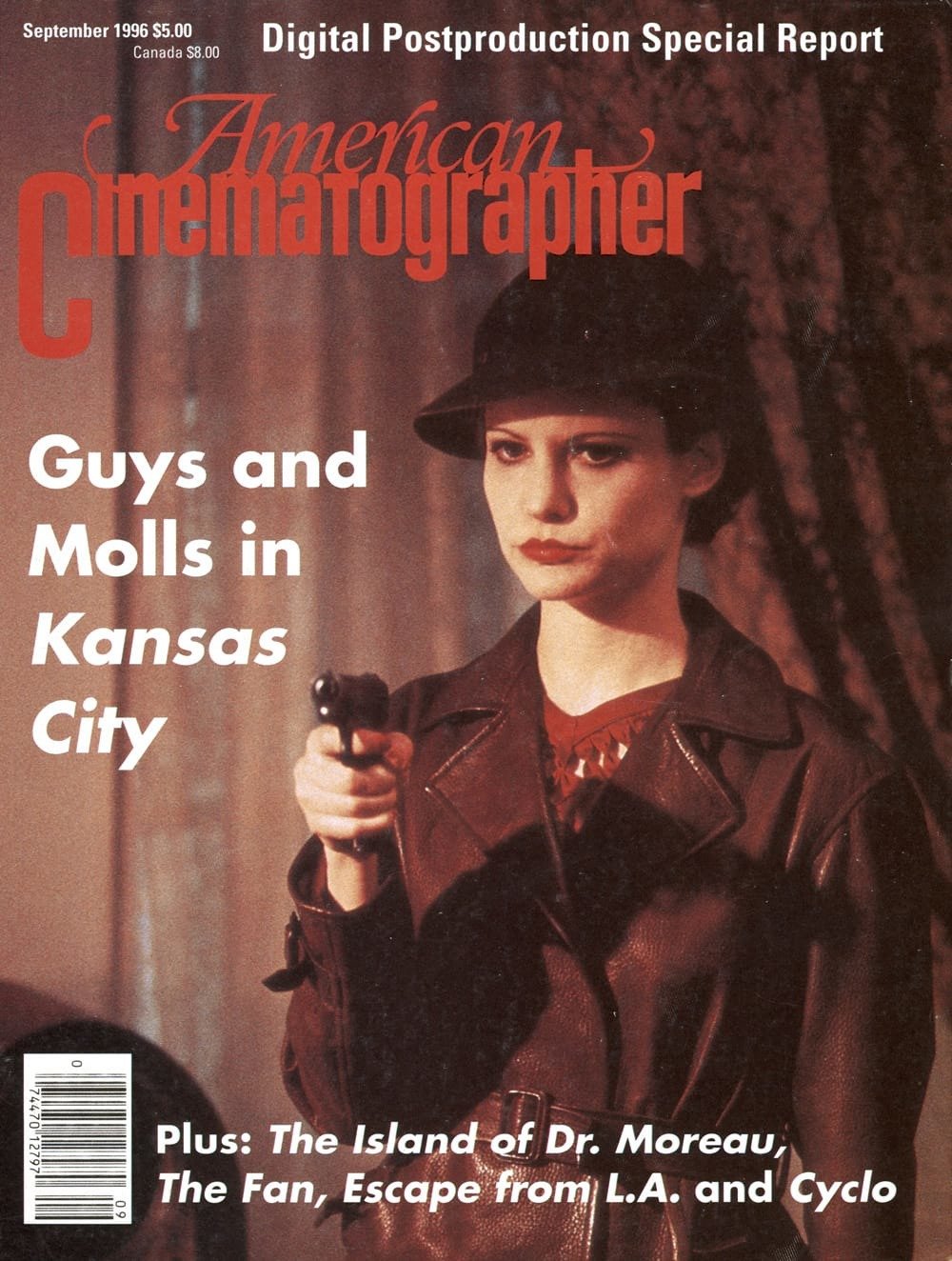

John Alton: Master of the Film Noir Mood

With such films as T-Men, Raw Deal and The Big Combo, the iconic cinematographer’s influential work formed the very foundation of the “dark film” style.

With such films as T-Men, Raw Deal and The Big Combo, the iconic cinematographer’s influential work formed the very foundation of the “dark film” style.

By Gary Gach

In the summer of 1923, five lads drove across the country full of optimism, joie de vivre, and the excitement of all things new. Upon arriving in California, they parked on Hollywood Boulevard, in front of the Egyptian movie palace. In the lobby, a Gypsy fortune teller read their palms. Each of them, she said, would seek his fortune elsewhere — save for the fifth lad. "You, I tell different," she said. "You'd better stay here. You're going to make it."

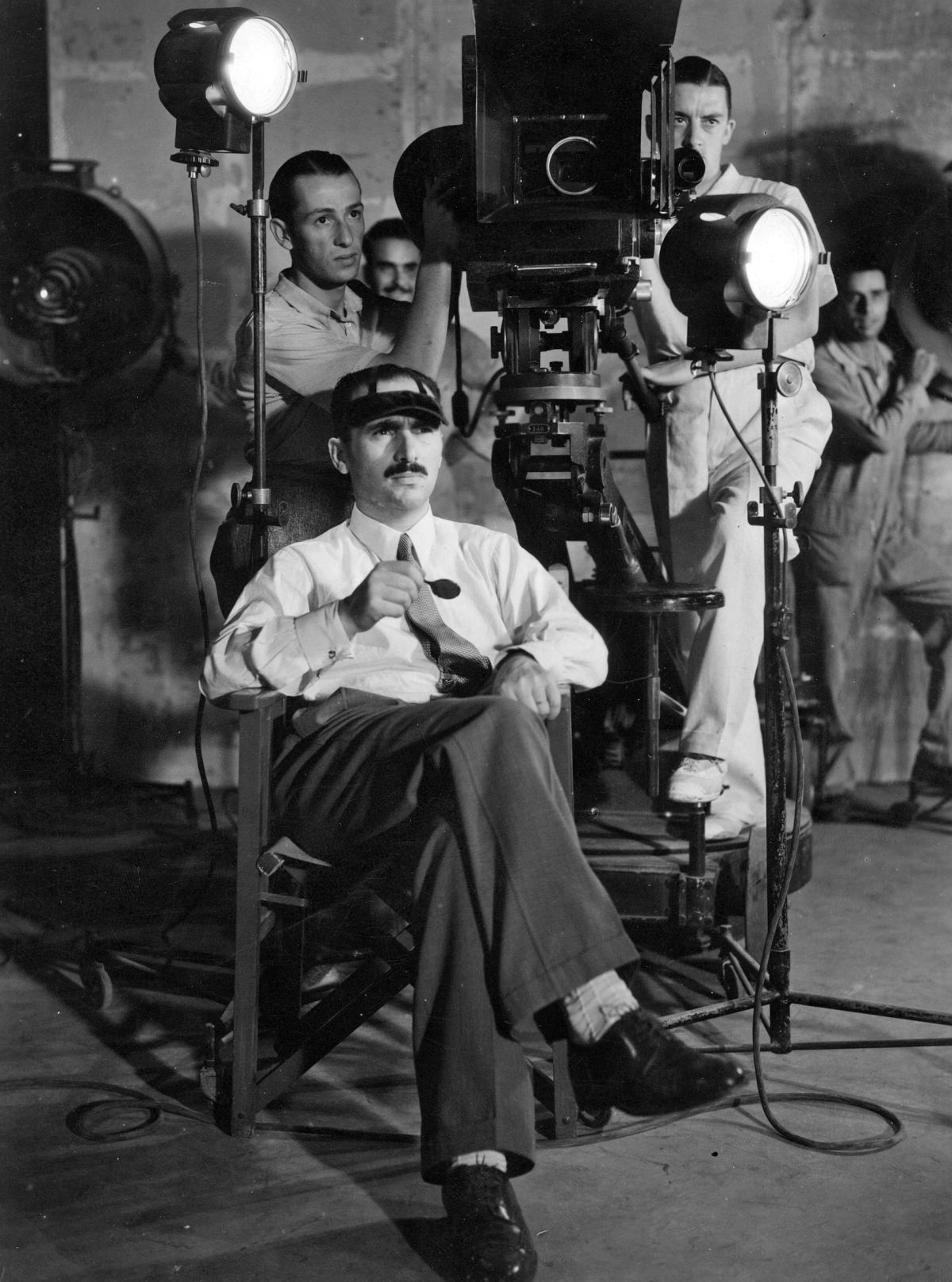

That lucky lad was John Alton, a cinematographer whose art has been lauded at recent film festivals in Vienna, Japan, Argentina, Telluride, and San Francisco, as well as in retrospectives at the American Museum of the Moving Image and the Pacific Film Archives. Alton's influential legacy was not always so celebrated, however; in fact, his achievements nearly slipped into oblivion before being rediscovered in the past several years.

Born in a castle in 1901, in a village on the Austrian border of Hungary, Alton lived to a ripe old age before dying on June 2, 1996 in Santa Monica. A child prodigy who sketched constantly, he had his own darkroom by the age of five. One day, he saw a man on the street grinding a little box; inside the box, pictures danced on a screen. The man explained, "These are motion pictures, pictures that move." Alton had never seen such a thing, and was instantly fascinated.

At 18, he set sail for New York to live with a prosperous uncle, and to take up studies in photochemistry. Alton soon found himself thrust into the movie business in his newly adopted city. "One day, I had the nerve to drop the books, and I went down to look at the pictures," he recalled. "I stopped at the gates of the Cosmopolitan Studio. All of a sudden a door opened, and a man grabbed me by the shoulders and said, 'Hurry up! We're waiting for you!'

"They put me in a dressing room, stuck me in a uniform, and put me next to Marion Davies, a big star at that time. At the end of the day, they gave me a check. Well, at home I used to get $1.50 a week, and here they gave me $12.50, for one day. So I lost my balance. They called me back the next day to work. I call it 'work,' but I just stood next to Marion Davies, the star. That's all I did! Then we went on location. In 30 days, I became a millionaire [by my standards]. I never went back to the college. I don't even know where I left the books!"

Having found work at the Paramount Studio lab, Alton soon saved enough cash to buy a car and venture to California. He landed his first studio job at MGM's recently bought Culver City lot, where he quickly became a cameraman.

Alton honed his cinematographic skills shooting Westerns for "Woody" Van Dyke, a man who valued the input of his cameramen and often defended their interests when no one else would. Van Dyke once said, "You fundamentally still have the old stereoscope as your basis to work from, but somebody's got to get that picture on the wall. It doesn't make any difference if that figure talks or sings; it's still a picture, and the picture will always be the basis of the movies. What you see with the eye is the important thing that governs your thinking and [that's] what people are looking at."

Alton next took charge of the camera department at Joinville Studios in Paris. He was soon trekking across Europe and Asia, where he shot short subjects and foreign-language features. In his spare time, he devoured music and books, and absorbed as much as he could of the art flourishing in museums and galleries, on movie screens, and on the streets.

In 1932, Alton was offered the opportunity to design and supervise a five-acre studio in Buenos Aires. The coming of sound had left the thriving Argentinean film industry high and dry, and he stayed there for six years. Within a month of his arrival, he married a former beauty queen-turned-journalist who had interviewed Alton aboard a ship during his passage to South America.

When he wasn't training crews or screening films at the studio, he wrote, directed, and produced a few features on his own. However, he remembered, "Every time I looked at a scene, I saw the light on the actors' faces and didn't hear [a word] they were saying, so I knew I wasn't going to be a director."

In 1939, the Altons migrated to Hollywood. He found work at RKO, Paramount and then Republic, averaging about four B-pictures a year. Despite his experience, he couldn't find a niche in A-films — perhaps because he appeared cocky to many. Remarked director Vincente Minnelli, "[People] interpreted John's continental poise as effete and arrogant. And to rough-and-ready American film crews, that could be the greatest affront of all."

After the freedom he had experienced in Argentina, the idea of changing careers and becoming a Hollywood producer was rather unappealing. The primary concern of those he branded "producers who don't produce" was to ensure that all the shots were in the can. As a cameraman, Alton preferred to plan his shots so that they would convey a film's shifting moods.

"In the morning, when many cameramen came in, they didn't have any plans for what they were going to do, so they just lit [everything] up," he said. "When I got a story, I'd sit down with the director and work out each scene — just the two of us. I'd ask the director his opinion of how he would like to see each scene. Then I'd go home and, even though it took me a lot of time, I'd work out every scene — [including] which lights and tricks to use. So when the time came for shooting, I was ready.

"But when I'd take most any director aside and ask him to sit down with me, he'd look at me as if I were crazy. He'd say, 'I've never sat down with a cameraman to talk about these things. What do you mean? You just pump a lot of light in!' I'd say 'You don't 'pump' light into a scene. That light has to tell something. There's a meaning, and it establishes a mood.' That was the difference between my pictures and some of the others: [in mine], each mood was different. The mood had to be done with lighting. That's my profession — not the lighting and how to light, but bringing out the mood."

Fate dealt Alton his winning card in 1947 when Republic assigned him to a fairly new director who had just joined the studio: Anthony Mann. Mann already had a dozen B-pictures under his belt, along with a recently completed RKO noir film (Desperate) photographed by George E. Diskant, ASC. Alton recalled thinking, "At last, here is a director I can really sit down and talk with." Thus began a collaboration that would define a high-water mark of pictorial storytelling; Alton and Mann worked together like guns and ammo.

Their first title, T-Men, was a crime procedural based on federal records, which the duo rendered in a noir stylization. Starring Dennis O'Keefe and Alfred Ryder as agents of the Treasury Department who infiltrate a counterfeiting ring, the film captured a new, post-war realism through its deft compositions, which offered compelling depth and space.

T-Men begins with a Treasury agent addressing the audience. The scene seems routine until one notices a small statuette of Abraham Lincoln that casts an exaggerated, ink-black shadow; the shadow undercut the traditional centrality of the speaking figure, and also provided a visual pun, implying that government agents were "shadowing" mobsters. Such shots, which were typical for Alton, would soon become standard noir fare.

The gangster genre, so popular during the Great Depression, used the underworld to mirror corruption on high. Reflective surfaces — glass-topped tables or puddles in the street — figure prominently in T-Men, and help to make the point that the honest agents are still a gang, just like their targets. This similarity helps the Feds to understand their prey, but it also gives them a hint of menace.

Another technique that draws the viewer into T-Men is the studied performances of the two actors portraying the story's stylishly dressed heroes, who operate undercover. From the moment they "cross the line," the agents communicate only through low-key glances. Particularly memorable is a quick close-up of O'Keefe flinching and lowering his head as off-screen gunshots signal the cold-blooded murder of his partner. Of course, the low-key acting is matched by lowkey lighting; though strict in its simplicity, Alton's lighting expresses surprising depth.

Another of the film's high points is the slaying of Schemer (Wallace Ford) in a steam room — a scene played out against the spooky strains of a theremin. Throughout the picture, the mystery of such locations as telephone booths, steam rooms and midnight waterfronts is heightened by their contrast to such everyday edifices as the offices of the Treasury Department and the Los Angeles Farmers' Market. Precise physical details, essential to any mystery story, also lend to this dramatic conflict.

Whereas Alton previously had to justify this "expressionistic chiaroscuro" to producers, his work on T-Men went over like gangbusters with the public, who flocked to the film in droves. From that point onward, he could promise a quickie dressed up to resemble a major production, and command A-picture salaries for his work on B-movies.

Perhaps it was for the best that Alton didn't get boxed into making just A-level films. As he himself once noted;

'When I go to retrospectives of my work, [they're not showing] the films that took us three months to make, but the little ones that took us two weeks. At MGM, we took three hours for a close-up. [But] at Republic, we often had only two or three weeks to make a picture. On some days we'd get 70 setups!"

After T-Men, Alton lent his touch to a dozen more pictures which, as a body of work, formed the apotheosis of the film noir style. In 1948, he shot five of these films: Canon City, The Amazing Mr. X. (a.k.a. The Spiritualist), He Walked by Night, Hollozu Triumph (a.k.a. The Scar), and Raw Deal.

In The Amazing Mr. X, Turhan Bey plays a charismatic psychic who preys on dowagers. Of particular interest to lighting buffs are the seance scenes lit by a crystal ball — which even include shots from the ball's perspective. Alton's lighting in these films was often an active, dramatic narrative element, and another striking moment in Mr. X is a quick shot of a character walking into a darkly lit room: the figure is definitely female, but it's difficult to ascertain whether the woman is a gullible widow or her suspicious sister.

On He Walked by Night, Anthony Mann took over the directing reins from Alfred Werker near the end of production. In the film, a thief turned cop-killer (Richard Basehart) eludes a police dragnet by hiding in the sewers of Los Angeles. The climactic chase scene prefigured inspired similar scenes in many subsequent films, most notably Carol Reed's The Third Man. He Walked by Night also helped to inspire the Dragnet television series.

Still, the richest, darkest and best of Alton's 1948 crop is Raw Deal. While T-Men, shot in Detroit and L.A., was made in some six weeks, Raw Deal shaved that production schedule in half. The latter film is a nightmare journey into the underworld, in which terror is contrasted with idyllic pastoral scenes. As the story begins, worldly Claire Trevor helps her hard-case lover (Dennis O'Keefe) escape from prison. His virginal pen pal (Marsha Hunt) gets mixed up in the escape, creating a twist on the usual romantic triangle. The characters also include a thug (John Ireland) and his boss (Raymond Burr), a mob kingpin given to dangerously smoldering moods. The crime angles keep the love triangle dynamic, and the narration (from Trevor's character) adds to the angularities.

In 1949, Alton made two more classics with Mann. MGM's Border Incident (featuring Ricardo Montalban, George Murphy and Howard da Silva) follows the "procedural" style of T-Men and He Walked by Night, as two agents infiltrate a mob involved in the exploitation of illegal labor from Mexico. In this film, Alton's exterior artistry is as expert as his interior work, with landscapes assuming an active importance. First-unit soundstage shots perfectly match the location work of the second-unit. Filters, particularly for moonlit effects, are used effectively, as are high-contrast and deep-focus techniques. Alton's light throughout is modulated yet harsh. Critic Manny Farber cites the film's climax, in which Murphy's character is mulched by a tractor and plow, as one of his favorite scenes in all of cinema.

Another classic from 1949, The Black Book (a.k.a. Reign of Terror), is an entertaining melange of genres — a "historical romantic action thriller." Yet again, an agent infiltrates a mob. In this case, the criminals are French Revolutionaries engaged in a plot to replace Robespierre with a more politically moderate candidate. Working with William Cameron Menzies as designer and Mann as director, Alton was inspired to pull off some of his most memorable shots, some of which seem three-dimensional. In one scene, the clever placement of 30 extras to look like a mob is a miraculous visual coup.

It was this kind of mastery that inspired writer Philip Kemp to submit that;

"...in the hands of a master like Alton, cinematography can on occasion take precedence over script, acting, and possibly even directing, in determining the key quality of the creative mix."

In the case of a picture like Black Book, it's tempting to imagine Mann acting as "ground control" (managing script, actors, crew and post-production) while extreme stylists Alton and Menzies concocted their spells for the actual images. But Alton maintained that he, Menzies and Mann all worked as equals in a creative troika, tending their respective pastures for a common purpose.

In the Hollywood of Alton's era, "art" was a dirty word, yet his compositions invariably beg comparison with such master painters as Rembrandt, da Vinci, de la Tour and Caravaggio. Alton admitted, "When I got an assignment, I read the script — or the book and the script — and then I went out to the art museums, even to Paris sometimes, to see what the masters had done. [On] The Black Book, I copied the masters.

"Nobody knew it, though. Some people knew that there was something going on [in my pictures], but not what. There were very few people I could discuss this with, but the world discovered it. [Audiences] noticed something different. They noticed that one scene was like this, one scene was like that. It was all worked out."

Film noir was a style that registered a certain social discontent before and after World War II. These films were offbeat dramas in which dark and light, good and evil, were touched by the finger of Fate and switched roles. Noir-style elements had cropped up in previous films, but the first to compose a complete noir syntax and grammar out of the expressionistic vocabulary was RKO's Stranger on the Third Floor (1940), photographed by Nicholas Musuraca, ASC.

The very term "film noir" was, in fact, an afterthought — a French term derived from the expression "roman noir" ("dark novel") which describes English Gothic fiction of the 19th Century.

In 1972, director Paul Schrader critically championed the form in his essay "Notes on Film Noir" in Film Comment. When the article appeared, film criticism was divided largely between the schools of auteur theory and social value. Schrader stressed visual style. His seminal essay singled out Alton as "the greatest master of noir... an Expressionist cinematographer who could re-light Times Square at noon if necessary." Comparing him to such predecessors as Fritz Arno Wagner and Karl Freund, ASC; Schrader observed that Alton transformed Expressionist techniques to a new generation that craved realism.

Three years later, the Berkeley-based Pacific Film Archives (PFA) scoured film depots and vaults for rare prints of the lesser-known films Alton had made at such long-defunct studios as Eagle-Lion, Monogram and Republic, and booked them with his more famous noirs. These widely circulated retrospectives helped increase awareness of Alton nationwide. In the March 1979 PFA calendar, filmmaker Dennis Jakob wrote, “Why do we feature John Alton? Simply because, with the growing appreciation of film noir as the most interesting style/genre of the post-war American cinema, it has become obvious that the director of photography is as important, even in many cases more important, than the director in creating the fatalistic mood and compositional tension which are the hallmarks of film noir expressiveness. And... Alton proved himself to be the greatest film noir cameraman of all time."

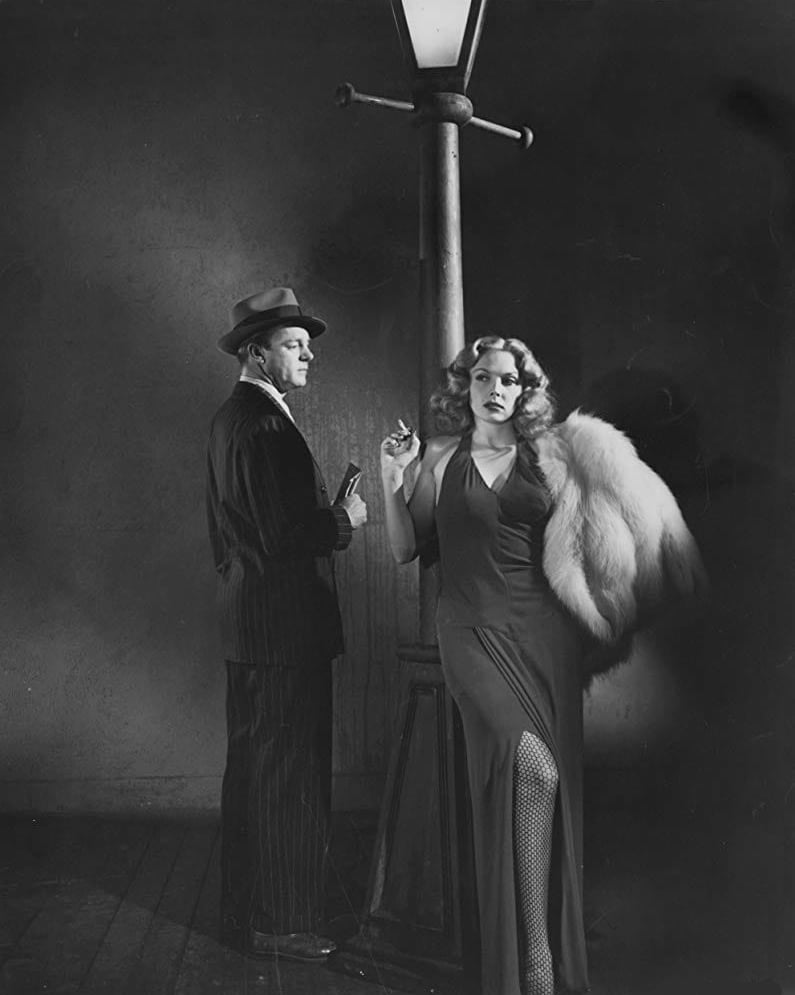

It helped that Alton wasn't "afraid of the dark," as he put it. In his swift lighting designs, he would establish a shot with only three lights, and then subtract one and then another. Alton de-emphasized the human form, making it an element within a mosaic of different visual events. To do this, he would often incorporate dark, negative space that Jakob called "an active aesthetic element in the frame."

Jakob has compared this aspect of Alton's art to that of Josef von Sternberg, ASC. "Theirs is an art of knowing what to reveal and what to conceal. What is concealed is heightened." Sometimes Alton would wrap a scene in ebony blackness (as if there were another frame within the frame of the screen) to invest its minimal patches of light with a higher intensity.

Having applied noir to the French Revolution in The Black Book, Alton used the style to great effect in Anthony Mann's admirable first Western, Devil's Doorway. Majestic images of man in nature, worthy of Ansel Adams, alternate with scenes so dark that at one point practically all that can be seen of Robert Taylor is his cheekbone and a glint of shirt buttons. The "frame within the frame" motif recurs throughout film, especially in one indoor image of a man and woman engaging in conversation with a gleaming window situated between them.

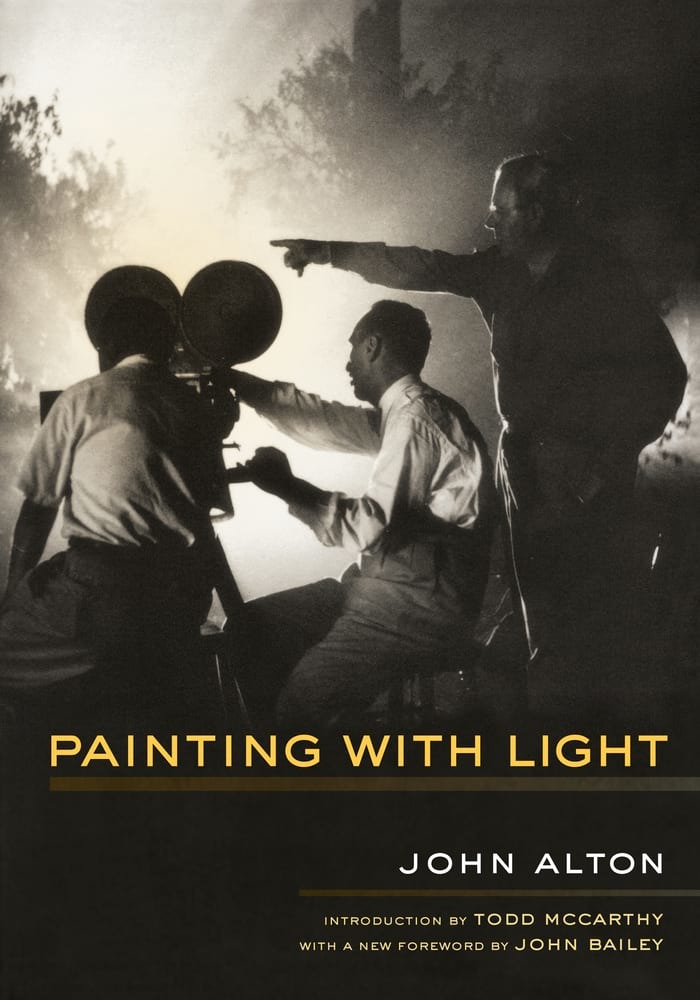

The year 1949 also saw the publication of Alton's book Painting with Light. A groundbreaking look at the camera's role in the making of motion pictures, the book was also the first written by a Hollywood cinematographer. Since 1930, Alton had been a contributor to International Photographer, so Painting was the fruition of both Alton's studio work and his journalism. The book later went out of print, but the critical re-evaluation of Alton's work led to its reprinting, and it is now a highly respected tome in cinematography circles.

In its pages, Alton maintained that films come in one of three categories: comedy, drama, and mystery. Mysteries, said Alton, allow a cameraman the chance to eschew "chocolate-covered" lighting and, instead, to light "100 percent naturally." "Naturalism," or "realism," refers to an experience such as a walk on foggy night that fills one with a certain sense of awe. Lighting fog, mist and smoke was an Alton specialty.

Noted Alton, "The most interesting things in the world happen at night. Of course, lighting, and light in itself, is a mystery!" Though he defined and diagrammed the essentials of cinematography in his book, he remained mute as to specifically how he had achieved his signature shots.

For some, Painting with Light left an indelible impression. Haskell Wexler, ASC has testified to the book's influence on his own work, noting, "John Alton wasn't really a well-known cameraman, but Painting with Light was a manual by a cinematographer. Most of the things [in the book] had to do with different kinds of lighting — ways of exciting you about ideas in light. Hard lighting. Perimeter lighting. From catwalks, up high. [When I first read it], I was shooting films in Chicago. It was the only contact I had with what Hollywood [cinematographers] did, and it provided my first visual comprehension [of that world]. I didn't know anything about gobos. I didn't realize that the big-time cameramen spent as much time taking things off as they did putting them on. The way I had to work, the problem was always to create enough light to get exposure for slow film and slow lenses. The ideas of double open ends and cutters, and of a cucoloris, were revealed to me in the book."

The text, which Alton had often scribbled in notebooks on the set, also captured some of the cultural life of its day. One subhead is entitled "What is thinking?" Elsewhere, he touched upon Chinese ideograms. He even compared photography to music: "A beautiful feminine close-up can be compared to a violin solo, and a strong characteristic picture of masculine beauty to a cello solo."

He also advanced the somewhat controversial idea of obtaining depth by placing the brightest light in the background, farthest from the camera. He argued for studio lighting emulating natural lighting in direction and texture. He proposed such innovations as an all-purpose conglomeration of lights arranged in a circular fashion, based on an apparatus (which he dubbed a "streamlight") that he had seen at the UFA Studio in Germany.

Alton eventually returned to MGM, where he'd already worked for 18 years. Over the next decade, he made some 34 films. The year 1950 marked the beginning of a creative relationship with director Vincente Minnelli. Their first picture together was Father of the Bride, shot in just 28 days. The story's wedding is all the more enchanting because it survives some harrowing detours, such as a series of unexpected late-night phone calls. The nightmare sequence, for which Minnelli expressly drafted Alton, is a visual tour de force; however, MGM was normally known for its polished look, so Alton invested most of the film with the light-hearted radiance of winsome, poignant comedy.

The next year, Minnelli tapped Alton for the ballet scenes in An American in Paris (1951). The cinematographer's mobile camera used over 20 different movements during that 17-minute sequence, and actively integrated the choreography. The lighting was equally intricate. Lighting setups often shifted abruptly in mid-shot, from noon to midnight or from blue to red. Matte paintings were used to re-create the Parisian skyline on the Culver City lot.

Alton's cinematography on the picture evoked the work of many famous painters, including Renoir, Utrillo, Rousseau, Van Gogh and Toulouse-Lautrec. A replica of the Place de Concorde (made of translucent plastic) was done up in the style of Dufy, and later serves as the site of the tale's climactic pas de deux. Recollected Alton, "The day after the film was finished, the producer, Arthur Freed, said to me, 'John, that's the first time photography saved a picture.'"

[Editor’s Note: You'll learn much more about Alton's work on An American in Paris — and the controversy around the Oscar win he shared with Al Gilks, ASC — here.]

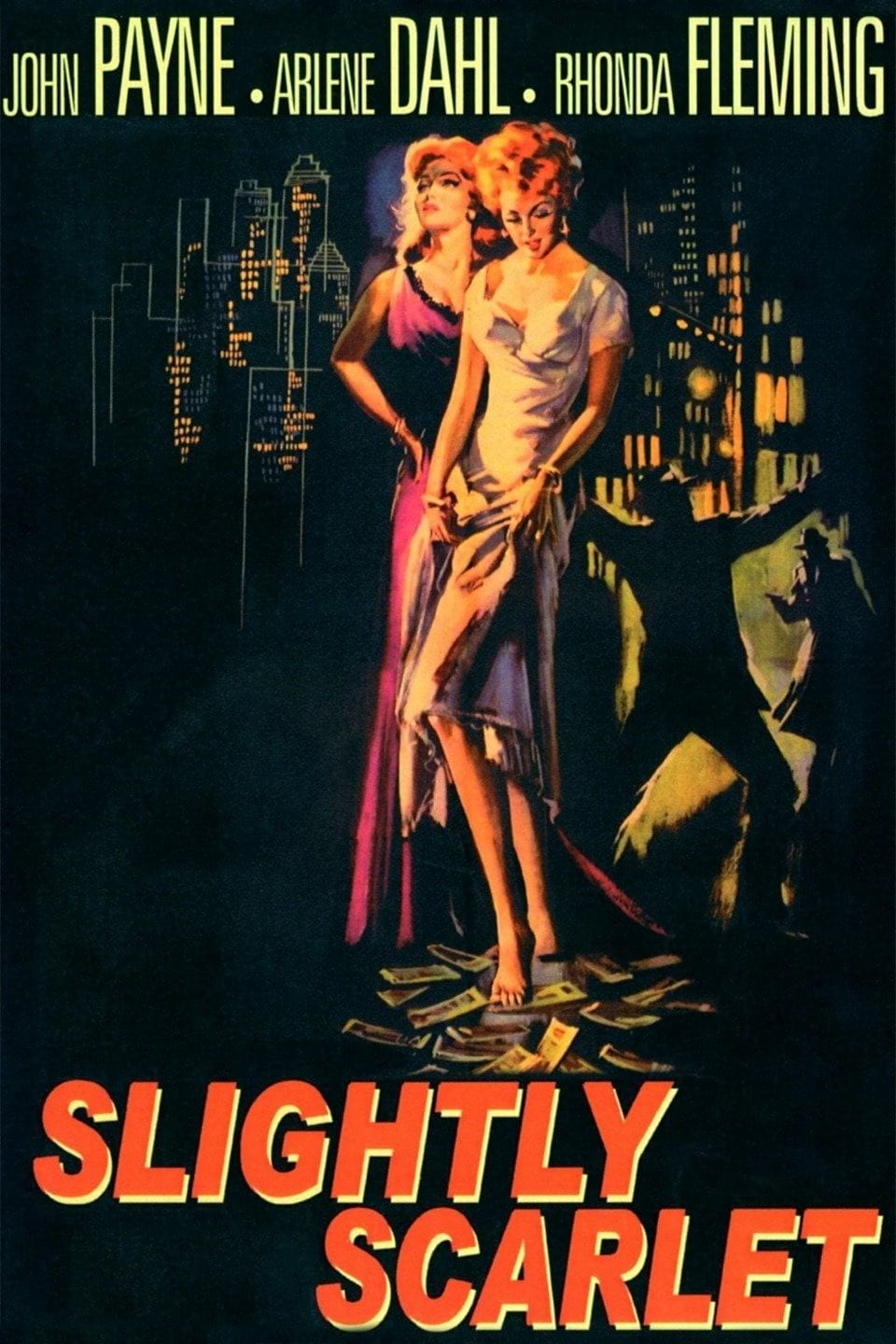

During the rest of the Fifties, Alton averaged about three pictures a year, and he even tried his hand at 3-D filmmaking. Of particular renown is Slightly Scarlet (1956), the last of six films he made with director Allan Dwan. Critic Andrew Sarris called it;

"... one of the most eye-boggling American movies ever made."

Bold, even lurid, in its color schemes and effects, the entire film resembles a Thirties-style pulp fiction illustration, but somehow its pyrotechnics lack the emotional punch of the cinematographer's black-and-white noirs. Alton himself said that he used black and white as colors in his work. "I could see more in the dark than I could in color," he said. Scarlet suffers in comparison to his work the previous year for director Joseph H. Lewis on The Big Combo, which presented a bitter, repressed world of menace and doom. In Combo, a deaf man being murdered sees the gunfire.

Elmer Gantry (1960) was Alton's last film of note. The narrative revelation of Gantry's worthlessness is underscored through "concealed lighting." Gantry roars with fire and brimstone — real, imagined and implied.

After Gantry, Alton decided to take a well-earned vacation. "I was tired of fighting [with the studios]," he confessed. "Mind you, I was fighting for their own good. I wanted to give them quality. The people making movies had one aim: to make money. I had one aim: to make beautiful pictures. It was time for me to move on."

In 1960, Alton abruptly quit the industry. He had already resigned from the ASC in 1944. (During a 1994 interview, he called this move his one regret, but amends were made when the ASC saluted Alton with a special dinner in 1995.) He continued to read voraciously and took up oil painting; he crafted over 100 small canvasses and then gave them all away.

Over the years, he remained a figure of mystery, even when critical recognition finally began to come his way. When the PFA was showcasing Alton's work, their officials didn't even know which continent he lived on. They had only received a letter from a forwarding post office that stated:

“There is no telling what part of the world I may be in... perhaps the southernmost tip of Argentina, the Galapagos Islands, or many other places Charles Darwin had visited before he wrote The Origin of the Species.”

In 1990, Todd McCarthy, Stuart Samuels, and Arnold Glassman began production on the cinematographic documentary Visions of Light. The filmmakers planned not only to sing Alton's praises, but to showcase some of his work. Though their attempts to interview him were thwarted (unbeknownst to Alton), the finished film — which included many striking examples of his work — lured the great cameraman out of his long exile. Alton attended the premiere and was hailed by dozens of contemporary luminaries of cinematography.

At the event, he summed up his achievements with the wisdom of his 94 years, exclaiming, "I took something, improved it, made something with it and I offered it on a platter for the public to enjoy."

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.

The Art Director’s Guild produced this short on Alton and his expert work with his key collaborators: